•

Table of Contents

click a title to go

directly to that section

Ho'okahi no la'au lapa'au, o ka mihi.

"The first remedy is forgiveness."

Hawaiian prayer

Introduction

In Hawai'i, the land, sky and ocean radiate healing to the world. The original Hawaiians practiced ho’oponopono (literally “to make things straight again”). Respecting that tradition, this small book is a living re-connection of all the peoples of modern Hawai'i and the first Hawaiians. We respect their original wisdom, and share it with the world.

Forgiveness has many faces. For the world cultures that have come to our islands in the center of the ocean, forgiveness is one of the keys to a meaningful life. Our community embraces forgiveness as a basic skill of life – the ability to be constantly renewed.

We weave forgiveness into the fabric of our personal, social, cultural, legal, economic, educational, and spiritual lives, reaching out to all the communities that make up Hawai'i today:

-

|

* exploring the roots of forgiveness in world religions, philosophies, history and the arts;

* hosting public conversations and sharing life experiences;

* providing information, ideas, connections and tools;

* honoring those who embody forgiveness in their lives;

* developing our personal understanding of forgiveness, and practicing what we learn. |

For America and for the world, we provide a heartfelt and practical connection to traditional Hawaiian ideals, with forgiveness at the center.

Michael North, Editor

Cover image: mahiole (feathered helmet) of a Hawaiian chief, from the collection of Captain Cook, shown at

the Honolulu Academy of Art, 2006

Other images here courtesy of Iona Contemporary Dance Theatre, Chris Spezzano, Malou Mallison, ‘Iolani Palace, Greenstar, Christian Science Monitor, Greater Good; WITH Forgiveness; all images and text remain the property of their respective copyright holders.

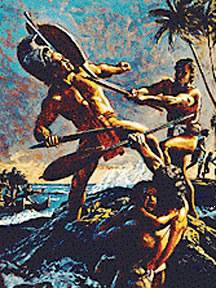

Law of the Splintered Paddle

King Kamehameha's Story: Hawai'i

King Kamehameha I, the first ruler of all the Hawaiian Islands, lived before European influence became strong in the central Pacific, from 1758 to 1819.

He had a reputation for independence, strength, justice and compassion -- combined with a fierce determination to unite the people of Hawai’i.

Kamehameha's proclamation of Mamalahoe -- the "Law of the Splintered Paddle," came about in a unique way. His story of compassion and forgiveness has been passed down through nearly two centuries, from Kingdom to Republic to Territory to State, and is included today in the Constitution of the State of Hawai’i.

The story goes like this:

The young royal warrior Kamehameha, headstrong with youth, was paddling a war canoe with his men near the shoreline of Ke'eau, in Puna, Maui. Seeking a place to rest, they came upon some commoners fishing on a beach, and attacked them. All escaped, except for two men who stayed behind to defend a man carrying a child on his back.

During the struggle, the young chief's foot caught in some lava rocks, and he was trapped there. One of the fishermen struck Kamehameha on the head with a paddle, and the paddle splintered. It was a blow that could have killed the young future King.

The man who hit him, in defending the child, allowed Kamehameha to survive. The young chief never forgot this act of forgiveness. This commoner taught Kamehameha that all human life is precious and deserves respect, that the strong must not mistreat the weak.

Kamehameha could have taken revenge on the fisherman, but he learned from the experience instead, and made forgiveness part of Hawai’i's heritage, and its future.

Years later, King Kamehameha I proclaimed Mamalahoe, the Law of the Splintered Paddle. It provides that any old person, woman or child may "lie by the roadside in safety." This means that anyone who is weak is entitled to protection and assistance, and to respect, even from the King.

Story suggested by Ramsay Taum, researched and written by the Hawai'i Forgiveness Project, from online sources at Kamehameha Schools, the University of Hawai’i Law School, and the State Constitution. For more, see http://www.hawaiiforgivenessproject.org/stories.htm#sources

Why to Forgive

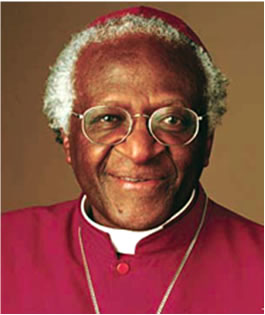

Archibishop Desmond Tutu

Malusi Mpumlwana was a young enthusiastic anti-apartheid activist and a close associate of Steve Biko in South Africa’s crucial Black Consciousness Movement of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He was involved in vital community development and health projects with impoverished and often demoralized rural communities.

As a result, he and his wife were under strict surveillance, constantly harassed by the ubiquitous security police. They were frequently held in detention without trial.

I remember well a day Malusi gave the security police the slip and came to my office in Johannesburg, where I was serving as general secretary of the South African Council of Churches. He told me that during his frequent stints in detention, when the security police routinely tortured him, he used to think, “These are God’s children and yet they are behaving like animals. They need us to help them recover the humanity they have lost.”

For our struggle against apartheid to be successful, it required remarkable young people like Malusi.

All South Africans were less than whole because of apartheid. Blacks suffered years of cruelty and oppression, while many privileged whites became more uncaring, less compassionate, less humane, and therefore less human. Yet during these years of suffering and inequality, each South African’s humanity was still tied to that of all others, white or black, friend or enemy. For our own dignity can only be measured in the way we treat others. This was Malusi’s extraordinary insight.

I saw the power of this idea when I was serving as chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. This was the commission that the post-apartheid government, headed by our president, Nelson Mandela, had established to move us beyond the cycles of retribution and violence that had plagued so many other countries during their transitions from oppression to democracy.

The commission granted perpetrators of political crimes the opportunity to appeal for amnesty by giving a full and truthful account of their actions and, if they so chose, an opportunity to ask for forgiveness —- opportunities that some took and others did not. The commission also gave victims of political crimes a chance to tell their stories, hear confessions, and thus unburden themselves from the pain and suffering they had experienced.

For our nation to heal and become a more humane place, we had to embrace our enemies as well as our friends. The same is true the world over. True enduring peace -- between countries, within a country, within a community, within a family -- requires real reconciliation between former enemies and even between loved ones who have struggled with one another.

In our commission hearings, we required full disclosure for us to grant amnesty. Only then, we thought, would the process of requesting and receiving forgiveness be healing and transformative for all involved. The commission’s record shows that its standards for disclosure and amnesty were high indeed: Of the more than 7,000 applications submitted to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, it granted amnesty to only 849 of them.

Forgiveness gives us the capacity to make a new start. That is the power, the rationale, of confession and forgiveness. It is to say, “I have fallen but I am not going to remain there. Please forgive me.” And forgiveness is the grace by which you enable the other person to get up, and get up with dignity, to begin anew. Not to forgive leads to bitterness and hatred, which just like self-hatred and self-contempt, gnaw away at the vitals of one’s being.

Whether hatred is projected out or projected in, it is always corrosive of the human spirit.

If peace is our goal, there can be no future without forgiveness.

Desmond Tutu, the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, retired as Archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa, in 1996. He then served as chairman of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This essay, originally printed in Greater Good magazine (http://www.greatergood.com) and edited for length here, draws from Bishop Tutu’s book, God Has a Dream (Doubleday, 2004).

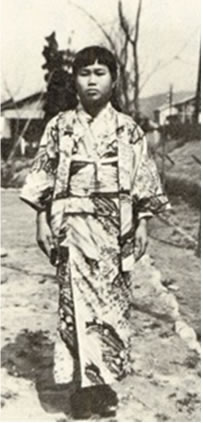

Sadako Sasaki

A Symbol of Peace

The paper crane is an international symbol of peace, because of a young Japanese girl named Sadako Sasaki, born in Hiroshima in 1943.

Sadako was two years old when the atom bomb was dropped on her city.

As she grew up, Sadako was a strong, courageous and athletic girl. In 1955, at age 11, while practicing for a big race, she became dizzy and fell to the ground. Sadako was diagnosed with leukemia, which became known as "the atom bomb" disease; cancer of the blood.

Sadako's best friend told her of an old Japanese legend, that anyone who folds a thousand paper cranes would be granted a wish. Sadako hoped that her wish would be granted: to get well so that she could run again.

She folded 654 cranes before she died. Her classmates also folded 346 cranes, so she was buried with one thousand paper cranes in 1955, at the age of twelve.

She never gave up. She continued to make paper cranes until she died.

Inspired by her courage, Sadako's friends and classmates put together a book of her letters and published it. They began to dream of building a monument to Sadako and all of the children killed by the atom bomb. Young people all over Japan helped collect money for the project.

In 1958, a statue of Sadako holding a golden crane was unveiled in Hiroshima Peace Park. The children also made a wish which is inscribed at the bottom of the statue and reads:

"This is our cry,

This is our prayer,

Peace in the world".

Today, people all over the world fold paper cranes and send them to Sadako's monument in Hiroshima. Today, people all over the world fold paper cranes and send them to Sadako's monument in Hiroshima.

Read an illustrated children’s version of a book about Sadako Asai: http://www.amazon.com/Sadako-Eleanor-Coerr/dp/0698115880

Here is the original adult version of a Sadako’s story, “A Thousand Paper Cranes”: http://www.amazon.com/Children-Paper-Crane-Struggle-Bomb/dp/1563248018

*

The Compassionate Monk

A story from the Dalai Lama

His Holiness the Dalai Lama visited Maui in April, 2007; thousands of people sat for hours in the tropical sun to hear his wisdom.

One story he told continues to resonate.

After the occupation of Tibet by the Chinese in 1949, many Buddhist monks were imprisoned for long years. They were sometimes subjected to great physical and mental hardships.

In 1962, as a gesture of goodwill, the Chinese released a senior monk who had been a close associate of the Dalai Lama. The old man made his way to Dharmsala, the city in northern India where the Dalai Lama maintains the Tibetan Buddhist tradition in exile.

The two men greeted each other warmly after such a long time apart, and the Dalai Lama said, “So, how are you, my friend?”

He responded, “Physically I am healthy. Mentally I am sound. But spiritually I was often in very great danger.”

Concerned, the Dalai Lama inquired what was the source of this spiritual danger.

The old man replied, “I was often in danger of losing compassion for my captors.”

The Dalai Lama nodded in silent understanding.

Saira and her Grandmother

One moment for forgiveness

Saira was three when she was hit by a car while walking across a street in Troy, New York with her mother. Months of surgery, recuperation, and therapy followed, but she never fully recovered.

Today, despite her confinement to a wheelchair and her inability to walk or use her arms and hands, Saira is a spunky young lady who dreams of becoming lead vocalist in her own rock band and founding a home for disabled children.

"I'm trapped outside, but free on the inside," she wrote in a recent issue of her school newspaper. "I probably do more than anyone else that can walk. Overall, being paralyzed isn't so bad."

But if you talk to grandmother (and primary caregiver) Alice Calonga, you'll get another angle:

“Saira's an inspiration. She doesn't have any animosity at all. She is a very positive human being, and doesn't dwell on what happened to her or feel sorry for herself. She's just a normal kid, as far as she's concerned. As much as was taken from her, she's given that much back a thousand times in her short life to the people around her.

“I'll never forget the first couple of days after the accident. There were two young men in the pediatric ICU who were always there, watching me. Finally one of them approached me and asked me if I was related to the little girl who got hit by the car. I said yes, I was her grandmother.

“I asked who he was, and he said he was the man who had hit her. I was stunned. Then he asked me if I could forgive him. When I tried to put myself in this stranger's shoes and think how devastated I would feel if I were him, I right away knew I had to forgive him. So I did. And I hugged him.

“At that moment my daughter came out of the ICU. She was horrified to see me talking with this man, and very angry at me. She started telling me how the accident had happened -- how the driver had been so impatient, he had driven around the vehicle in front of him, which had stopped for a traffic light, and run into her and Saira. Then, trying to flee the scene, he had accelerated and hit Saira a second time, breaking her neck and crushing her spine.

“At first I couldn't believe it. I said, ‘Nobody would do something like that.’ But I found out that my daughter was not exaggerating. I was so horrified, I felt like I had been raped. I had been robbed of my forgiveness by a man who wasn't the least bit entitled to it.”

Alice says that despite her shock -- and the fury of her daughter, who told her she had no right to forgive anyone for what happened -- she is certain she did the right thing.

“As angry as some people are that I did it, in my heart I know I forgave that driver for the right reason, even if I was just going on instinct. I can honestly say that if I had not forgiven him at that moment, I might never have been able to. It's so clear to me now that he didn't deserve it. But if I were him -- if I had done what he did -- I know I would still want forgiveness. That's how I was thinking when I originally forgave him.”

Edited and reprinted from Why Forgive?

Ebook by Johann Christoph Arnold; www.bruderhof.com.

Copyright 2003 by The Bruderhof Foundation, Inc.; used with permission.

from http://www.withforgiveness.com

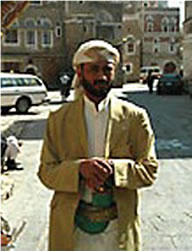

Militant poetry:

Art and Tolerance in Yemen

Amin al-Mashreqi is taking on Al Qaeda -- with his poetry.

As the dusk call to prayer fades in Sanaa, Yemen, Amin al- Mashreqi glances at the expectant faces surrounding him and begins to read from his slim, handwritten book of verse that is helping to bring a measure of peace to this mountainous Arab country:

O, you who kidnap our guests,

Your house will refuse you,

These violations are against Islam

Crammed into a mud-brick shop, his audience, some with their hands resting on their gold-trimmed daggers, listen to his verse denouncing violence and Islamic militancy. When he finishes, there is silence. Then the room erupts in applause.

"Other countries fight terrorism with guns and bombs, but in Yemen we use poetry," says Mr. Mashreqi later. "Through my poetry I can convince people of the need for peace who would never be convinced by laws or by force."

For years Yemen has been known as a breeding ground for extremism. It is the ancestral homeland of Osama bin Laden and where Al Qaeda bombed the USS Cole in 2000. But today this country is quietly winning a reputation for using unorthodox tactics to take on Islamic militancy.

"Yemen has turned to poets because they are able to speak to diverse groups of people who the literati and the elite cannot reach," explains W. Flagg Miller, professor of Anthropology and Religious Studies at the University of Wisconsin who has studied Yemeni poetry for about 20 years.

"There is a long tradition of leaders turning to poets right across the Arab world," explains Dr. Miller. "The prophet Muhammad himself worked with a poet, Hassan ibn Thabit, to spread the word and compose poetry against other poets and tribes who refused to acknowledge Islam." "There is a long tradition of leaders turning to poets right across the Arab world," explains Dr. Miller. "The prophet Muhammad himself worked with a poet, Hassan ibn Thabit, to spread the word and compose poetry against other poets and tribes who refused to acknowledge Islam."

After seeing the devastation and violence of the USS Cole bombing, the militant Mashreqi was troubled . His friend, Sanabani, saw him as a man transformed.

"He came back with the most beautiful poetry I have ever seen," says Sanabani, recalling his amazement at the poet's new verses that now condemned violence and promoted peace and tolerance.

Sanabani and Mashreqi realized that the historic respect accorded to poets gives them a unique power to win over illiterate tribesmen in remote areas where villagers are traditionally skeptical of all that the government has to say and offer.

"The Yemeni people are very sensitive to poetry -- especially traditional poetry like this," says Mashreqi. "If poetry contains the right ideas and is used in the right context, then people will respond to it because this is heart of their culture."

O men of arms, why do you love injustice?

You must live in law and order

Get up, wake up, or be forever regretful,

Don't be infamous among the nations

adapted from an article by James Brandon, Correspondent of The Christian Science Monitor May, 2006

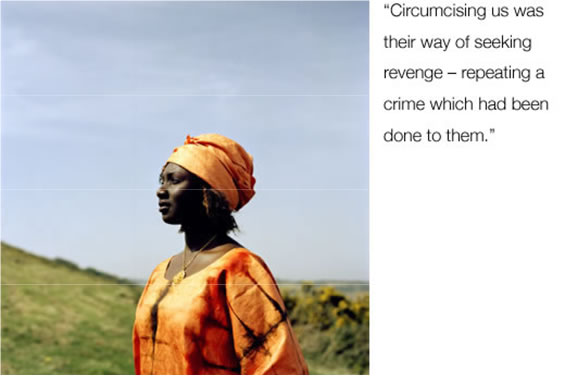

Salimata Badji-Knight

Forgiveness through the pain

Salimata Badji-Knight, 37, was brought up in a Muslim community in Senegal, where she was circumcised at the age of five. She moved to Paris when she was nine, and has spent most of her adult life campaigning to prevent the practice of female circumcision in African cultures.

I was five when the women from my village said we were going into the forest. There was a whole group of us girls aged between five and 16; we were happy because we thought we were going for a picnic. But it wasn’t a picnic.

Even more than the pain and the crying, I remember the shock of realising that they’d tricked us. I knew they had cut something from me, but I didn’t know what. The women were kind in their way, giving us sweets and nice food; it was their way of asking for forgiveness. But it was also their way of seeking revenge – repeating a crime that had been done to them.

Only later, when I was a teenager, did I realise what had happened. We had been circumcised, supposedly to make us cleaner and to stop us having boyfriends. For my parents it was like preparing me for marriage – they were doing it for my own good and I accepted this because circumcised Muslim women have stature and respect.

Later, when I came to live in Paris, it was a shock to discover that this was not something that happened to everyone. I was horrified to see Senegalese girls being told they were going on holiday to Africa, when in fact they were being taken back to be circumcised. For my mother it was a normal part of her culture, and in Paris she secretly had three of my younger sisters circumcised.

I was full of rage and was determined to stop this brutal practice. I started to talk to anyone who would listen: the social services, doctors, the police and other Africans living in Paris.

For a long time I blamed all the women in my community who had united to do this to me, and I blamed all the men for standing by and allowing it to happen. I blamed my mother because she condoned it, and my father because he had never been there to stop it.

When I discovered that most people believe female circumcision to be a terrible wrong, I felt suicidal. Circumcision takes away your identity and your dignity. It was only when I became a Buddhist and stopped viewing myself as a victim that I stopped feeling unworthy. Out of rage came compassion, and the realisation that this was not my mother's fault, nor the fault of the women who had done this to me. They were simply blinded by tradition.

If I’d held on to all that anger and blame, I’d be dead by now. But my anger has had great results, because it has made me fight to stop this practice. I now work with a campaign ground called Forward, and I speak at schools both in the UK and France.

Before he died six years ago, I was able to have a good talk with my father. I opened my heart to him and explained how female circumcision could affect you physically and mentally. He cried and said that no woman had ever explained the suffering to him. Then he apologised and asked for forgiveness.

The next day he called my relatives in Senegal and told them to stop the practice. As a result, a meeting that was scheduled for young girls to be circumcised was cancelled, and 50 girls were saved.

Immaculée at St. Ann’s Church

Kaneohe, Hawai’i; Feb.16, 2007

Immaculée Ilibigaza, Rwanda

Genocide and Forgiveness

Immaculée Ilibigaza hid for three months in a tiny room with seven other women, huddled in silence while cold-blooded killers lurked nearby, calling her name:

"I have killed 399 cockroaches,” they chanted. “'Immaculée will make 400. It’s a good number to kill.”

The Rwandan holocaust claimed the lives of nearly a million people. One remarkable woman survived the slaughter by finding shelter in the confines of a small bathroom. Immaculée transformed her life, and even forgave the people who had murdered her entire family – some of whom were neighbors.

She told her story, in early 2007 at a church in Kaneohe, Hawai’i.

After a long struggle with hate, she had decided that she could not live without forgiving. This is what happened when she met one of the killers of her family:

Everything was gone; everything we had, my family themselves … gone.

But somehow there was a strong hand, I could feel it holding me inside, telling me, “If you are strong, I am with you. Keep the love inside. And don’t change your mind about forgiving.” It was like I went to sleep one night and knew one truth, and woke up the next morning to know a different truth. I couldn’t hate anymore.

I remember one day, someone called me and said, if I wanted to see one of the men who killed my parents, he was in prison. To tell the truth, I was scared. I didn’t know if I would jump on him, if I would change my mind…if this forgiveness idea was just a mechanism of survival.

I accepted and went to the prison. The head of the prison was a survivor also. They brought the man out, I remember him coming to the door; he had lost weight, his hair had fallen out. I remembered this face; this man used to be so well-dressed, with his suit, his family nearby, children who were my age. He was a teacher, someone very respected in our village.

When I saw him, I couldn’t imagine – why someone would choose this, from what was. It made me think back to when I was still shut up in that bathroom – he cannot know what he is doing. He had brought this future to his children, and to me? There was such blindness, I wanted to shake him, to wake him up – to say “The truth is, if you had only acted with some love, it would have been different for you – for everybody.”

Of course I couldn’t say those words, but I truly had compassion, strangely – as strange as can be – and I started to cry. The head of the prison said, “What’s wrong with you? How can you think about him – what makes you cry?”

I said to the man who was with me – “I forgive him. I want him to learn, to find the truth inside his heart – so he knows that my heart is not in the hating part of him. So that he can be free.”

The head of the prison asked, “How can you even think of doing this?”

I answered, “All there is in my heart now is forgiveness. Everything else is stripped away.”

One year ago, I met the head of the prison again. He said, “You don’t know what you did to me. You changed my life. Just to see you, teaching and having compassion for that killer, changed the way I looked at life. I used to get my only satisfaction from beating up those prisoners. And now I understand – it is possible to react differently.”

|

Immaculées full story is told in her book, Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust. Details at http://www.lefttotell.com

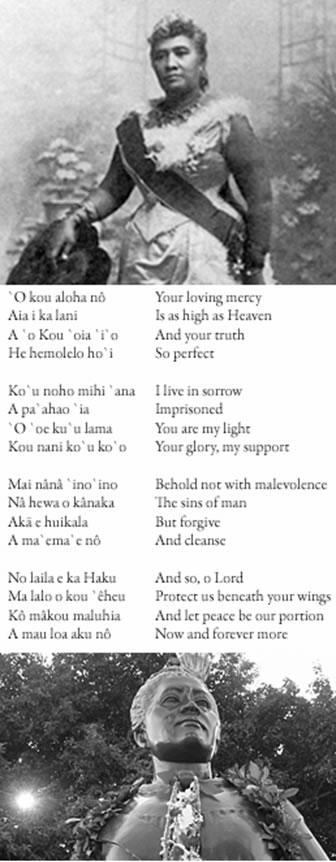

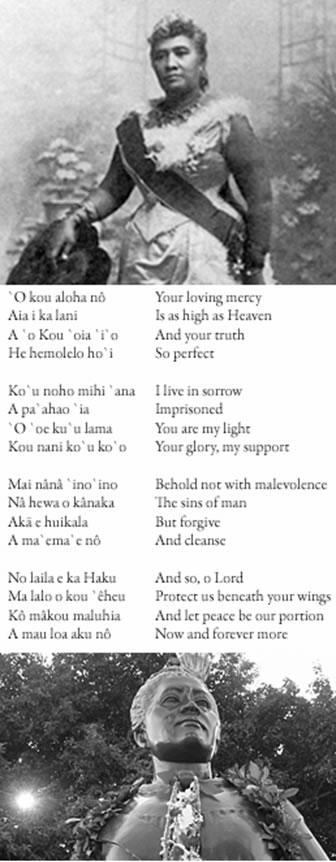

Queen Lili’uokalani Queen Lili’uokalani

Dignity of a Prayer

Charged with treason by a group of businessmen from America and forcibly deposed by a landing of the United States Marines, Queen Lili’uokalani waited, imprisoned in her own home at 'Iolani Palace in Honolulu.

During this time she wrote a simple poem, which has become known as the Queen's Prayer -- and stands today as a witness to the strength and dignity of the Hawaiian people, and the power of forgiveness. Her words long outlive her captors.

Here is part of her story, written in the Queen's own words, from "Hawai'i's Story by Hawai'i's Queen" by Liliuokalani, 1898

CHAPTER XLIV: IMPRISONMENT – FORCED ABDICATION

FOR the first few days nothing occurred to disturb the quiet of my apartments save the tread of the sentry. On the fourth day I received a visit from Mr. Paul Neumann, who asked me if, in the event that it should be decided that all the principal parties to the revolt must pay for it with their lives, I was prepared to die? I replied to this in the affirmative, telling him I had no anxiety for myself, and felt no dread of death. He then told me that six others besides myself had been selected to be shot for treason, but that he would call again, and let me know further about our fate...

The idea of abdicating never originated with me. I knew nothing at all about such a transaction until they sent to me, by the hands of Mr. Wilson, the insulting proposition written in abject terms. For myself, I would have chosen death rather than to have signed it; but it was represented to me that by my signing this paper all the persons who had been arrested, all my people now in trouble by reason of their love and loyalty towards me, would be immediately released. Think of my position – sick, a lone woman in prison, scarcely knowing who was my friend, or who listened to my words only to betray me, without legal advice or friendly counsel, and the stream of blood ready to flow unless it was stayed by my pen.

My persecutors have stated, and at that time compelled me to state, that this paper was signed and acknowledged by me after consultation with my friends whose names appear at the foot of it as witnesses. Not the least opportunity was given to me to confer with any one; but for the purpose of making it appear to the outside world that I was under the guidance of others, friends who had known me well in better days were brought into the place of my imprisonment, and stood around to see a signature affixed by me....

So far from the presence of these persons being evidence of a voluntary act on my part, was it not an assurance to me that they, too, knew that, unless I did the will of my jailers, what Mr. Neumann had threatened would be performed, and six prominent citizens immediately put to death. I so regarded it then, and I still believe that murder was the alternative. Be this as it may, it is certainly happier for me to reflect to-day that there is not a drop of the blood of my subjects, friends or foes, upon my soul... So far from the presence of these persons being evidence of a voluntary act on my part, was it not an assurance to me that they, too, knew that, unless I did the will of my jailers, what Mr. Neumann had threatened would be performed, and six prominent citizens immediately put to death. I so regarded it then, and I still believe that murder was the alternative. Be this as it may, it is certainly happier for me to reflect to-day that there is not a drop of the blood of my subjects, friends or foes, upon my soul...

It is a rule of common law that the acts of any person deprived of civil rights have no force nor weight, either at law or in equity; and that was my situation. Although it was written in the document that it was my free act and deed, circumstances prove that it was not; it had been impressed upon me that only by its execution could the lives of those dear to me, those beloved by the people of Hawaii, be saved, and the shedding of blood be averted. ...

After those in my place of imprisonment had all affixed their signatures, they left, with the single exception of Mr. A. S. Hartwell. As he prepared to go, he came forward, shook me by the hand, and the tears streamed down his cheeks. This was a matter of great surprise to me. After this he left the room. If he had been engaged in a righteous and honorable action, why should he be affected? Was it the consciousness of a mean act which overcame him so?

All of the Queen's words, "Hawai'i's Story by Hawai'i's Queen" – a vital witness to Hawaiian history -- may be read here for free: http://snipurl.com/liliuokalani

Here is a link to purchase the book: http://snipurl.com/hawaiisqueen

Sound of Forgiveness

An exercise developed by the Hawai’i Forgiveness Project

0. Print this exercise, with the nine quotes that follow – each quote separately, on its own page. Settle your mind, and gather a group.

1. Explain that this is a simple exercise, developed by the Hawaii Forgiveness Project based on a very old Quaker practice from Pennsylvania. Ask for the whole group’s support in finding our common root. Ask for nine volunteers.

2. Hold the nine pieces of paper in your hands silently, without looking at them. Keeping them face down, walk slowly and thoughtfully to nine people who seem ready, and give each person the paper you feel belongs to them. Explain what you are doing. 2. Hold the nine pieces of paper in your hands silently, without looking at them. Keeping them face down, walk slowly and thoughtfully to nine people who seem ready, and give each person the paper you feel belongs to them. Explain what you are doing.

3. Ask the first person you approached to read their paper, silently. Then ask them to read it aloud, twice.

4. Now say this, in your own words, to the reader:

“Just sense the words as a voice, as a series of pure sounds, and let them roll through you without resistance for a moment.”

“Don't think about whether you agree intellectually with the words you’ve read. Don't think about whether you understand them fully. Don't support or argue with them from your experience.”

Now please read them once more, silently."

5. Wait until the silence settles. Ask the person this question:

"How do these words made you feel? What feeling lies beneath these words for you, right now?"

Ask the person to answer, using as few words as possible -- simple words, stated in a simple way. Wait for the answer, without comment or discussion.

6. Ask another question:

"Do you see any images, recall any memories, any places, people or faces, as you hear these words? What sensations lie beneath these words for you, right now?"

Wait for the answer, and receive it in silence. Ask others to do the same.

7. Ask the person to carry his or her paper with them all day, to get it out when they think of it, and to gently consider its message. To notice how it is reflected in the events of the day as they unfold.

8. Move on to the next person. Repeat the process up to three times with three different people. Each person should take just five minutes or so.

9. When finished, ask the other six people to pass around the six passages that were unread, and let everyone read them. Invite group discussion.

Total time: 20 minutes

Quotes for the Sound of Forgiveness Exercise:

Please print one quote on each page for the exercise.

The less you open your heart

to others, the more your heart suffers.

-- Deepak Chopra

Holding onto anger

is like grasping a hot coal

with the intent of throwing it

at someone else;

you are the one

who gets burned.

-- Buddha

Greater in battle

than the man

who would conquer

a thousand-thousand men

is he who would conquer

just one: himself.

-- Buddha

In forgiveness, we realize we need forgive only ourselves.

We are forgiving a dream we made up –

to run from God and play God in our own world....

We forgive everyone and everything, continuously.

We forgive God.

We forgive ourselves.

-- Chuck Spezzano

I have come to the frightening conclusion that I am the decisive element.

It is my personal approach that creates the climate.

It is my daily mood that makes the weather.

I possess tremendous power to make life miserable or joyous.

I can be a tool of torture or an instrument of inspiration; I can humiliate or humor, hurt or heal.

In all situations, it is my response that decides whether a crisis is escalated or de-escalated, and a person humanized or de-humanized.

If we treat people as they are, we make them worse. If we treat people as they ought to be, we help them become what they are capable of becoming.

-- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Vitality shows

not only in the ability to persist,

but in the ability to start over.

--F. Scott Fitzgerald

We have flown the air like birds

and swum the sea like fishes,

but have yet to learn

the simple act of walking

the earth like brothers.

-- Martin Luther King, Jr

Forgiveness is the fragrance that the violet sheds

on the heel that has crushed it.

–Mark Twain

Forgive me my nonsense

as I also forgive the nonsense of those

who think they can talk sense.

-- Robert Frost

Nail in the Fence

There once was a little boy who had a bad temper. His father gave him a bag of nails and told him that every time he lost his temper, he must hammer a nail into the back of the fence.

The first day the boy had driven 37 nails into the fence.

Over the next few weeks, as he learned to control his anger, the number of nails hammered daily gradually dwindled down. He discovered it was easier to hold his temper than to drive those nails into the fence.

Finally the day came when the boy didn't lose his temper at all. He told his father about it and the father suggested that the boy now pull out one nail for each day that he was able to hold his temper.

The days passed and the young boy was finally able to tell his father that all the nails were gone. The father took his son by the hand and led him to the fence.

He said, "You have done well, my son, but look at the holes in the fence. The fence will never be the same. When you say things in anger, they leave a scar just like this one. It won't matter how many times you say I'm sorry, the wound is still there."

Forgiveness is seeing the nail, drawing it out, and thanking the one who drove it in, for the valuable lesson he made possible. Forgiveness is seeing the nail, drawing it out, and thanking the one who drove it in, for the valuable lesson he made possible.

(anonymous)

The Meaning of Forgiveness

in world literature

Behold not with anger the sins of man, but forgive and cleanse...

Mai nana`ino`ino

Na hewa o kanaka

Aka e huikala

A ma'ema`e no...

-- Queen Lili’uokalani, the last Queen of Hawai'i; 1893

Henry Kapono, speaking about his album The Wild Hawaiian on which he sings a version of the Queen's Prayer:

“She’s one of my favorite songwriters and such a courageous leader. In this song she was saying, though things happened and it might not have been right, we've got to forgive. If we don't do that we will never be able to perpetuate our culture. In some ways it was saying to me if we can do this we can free her. Our images of her are of her in prison and we can let go of that and set her free. The universal truth is that if we don't forgive people we never move on.”

Ho'okahi no la'au lapa'au, o ka mihi.

The first remedy is forgiveness.

-- Kupuna Alapa'i Kahu'ena, La'au Lapa'au

Allow yourself to yield, and

You can stay centered.

Allow yourself to bend, and

You will stay straight.

Allow yourself to be empty, and

You will be filled.

-- Lao Tzu

You cannot shake hands with a clenched fist.

-- Indira Gandhi

The ignorant neither forgive nor forget; the naive forgive and forget; the wise forgive but do not forget.

-- Thomas Szasz

Turn your face to the sun and the shadows fall behind you.

-- Maori proverb

"Act as if the principle by which you act were about to be turned into a universal law of nature".

--Immanuel Kant

"The world shrinks or expands in proportion to one's courage."

--Anais Nin

Humanity is never so beautiful as when praying for forgiveness, or else forgiving another.

--Jean-Paul Richter

To forgive oneself? No, that doesn't work: we have to be forgiven. But we can only believe this is possible if we ourselves can forgive.

--Dag Hammarskjold

And if your friend does evil to you, say to him, I forgive you for what you did to me, but how can I forgive you for what you did to yourself?

-- Friedrich Nietzsche

We all like to forgive, and love best not those who offend us least, nor who have done most for us, but those who make it most easy for us to forgive them.

-- Samuel Butler

We ask God to forgive us for our evil thoughts and evil temper, but rarely, if ever ask Him to forgive us for our sadness.

-- R. W. Dale

Love thy neighbor as thyself: Do not to others what thou wouldn't not wish be done to thyself: Forgive injuries. Forgive thy enemy, be reconciled to him, give him assistance, invoke God in his behalf.

-- Confucius

They who forgive most shall be most forgiven.

-- Josiah Bailey

Always forgive your enemies -- nothing annoys them so much.

-- Oscar Wilde

Forgiveness does not change the past, but it does enlarge the future.

-- Paul Boese

Anger ventilated often hurries towards forgiveness; anger concealed often hardens into revenge.

-- Edward G. Bulwer-Lytton

Forgive him, for he believes that the customs of his tribe are the laws of nature!

-- George Bernard Shaw

The heart of a mother is a deep abyss, at the bottom of which you will always find forgiveness.

-- Honore De Balzac

To be able to bear provocation is an argument of great reason, and to forgive it of a great mind.

-- John Tillotson

Never does the human soul appear so strong and noble as when it forgoes revenge and dares to forgive an injury.

-- Edwin Hubbel Chapin

An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and the whole world will be blind and toothless.

-- Mahatma Gandhi

thanks to Clyde Musgrave of Dallas, Texas for helping to research and assemble these quotations

Shu – Forgiveness

“soft as the speaking heart”

The Hawai’i Forgiveness Project has used this symbol for several years, and people ask us about its origins.

The Chinese character Shu is comprised of three symbols, which interact to produce subtle meanings.

The upper part of the character is Ru, meaning "like, as or same."

If you break this down, the left part is Nui, meaning "woman," representing "softness."

The right part is Kou, which commonly means a squire or servant; its root meaning is "mouth" or "speak."

The bottom part of the character is Xin, meaning "heart."

If you translate the whole character Shu into English directly, the common Chinese meaning today is "forgive from the heart."

Deeper meanings, which might be discovered in poetry and sacred literature, are "like a woman who speaks from the heart," or "soft as the speaking heart."

Translation and commentary by Ruby Khalsa, Beijing and Hawai’i; from the Hawaii Forgiveness Project, http://www.hawaiiforgivenessproject.org

Forgiveness Stories

Edited by Michael North

Hawaii Forgiveness Project 2007

website: http://www.hawaiiforgivenessproject.org

this book, and condensed versions, may be downloaded at no charge here:

http://www.hawaiiforgivenessproject.org/stories/

permission to reprint and redistribute this document,

in print or digital form, is freely granted to all,

provided it is unaltered

book and website produced with the assistance of:

Cades-Schutte, Honolulu, HI

http://www.cades.com

Greenstar, Haleiwa, HI

http://www.greenstar.org

Jade and Arts, Kailua, HI

http://www.jadeandart.com

The Copy Hut

http://www.copyhut.biz

thanks to Roger Epstein, Merton Chinen,

Xiao Fang Zhou, Mercedes Khalsa, Clyde Musgrave, Eric Lyon

|

Queen Lili’uokalani

Queen Lili’uokalani So far from the presence of these persons being evidence of a voluntary act on my part, was it not an assurance to me that they, too, knew that, unless I did the will of my jailers, what Mr. Neumann had threatened would be performed, and six prominent citizens immediately put to death. I so regarded it then, and I still believe that murder was the alternative. Be this as it may, it is certainly happier for me to reflect to-day that there is not a drop of the blood of my subjects, friends or foes, upon my soul...

So far from the presence of these persons being evidence of a voluntary act on my part, was it not an assurance to me that they, too, knew that, unless I did the will of my jailers, what Mr. Neumann had threatened would be performed, and six prominent citizens immediately put to death. I so regarded it then, and I still believe that murder was the alternative. Be this as it may, it is certainly happier for me to reflect to-day that there is not a drop of the blood of my subjects, friends or foes, upon my soul... 2. Hold the nine pieces of paper in your hands silently, without looking at them. Keeping them face down, walk slowly and thoughtfully to nine people who seem ready, and give each person the paper you feel belongs to them. Explain what you are doing.

2. Hold the nine pieces of paper in your hands silently, without looking at them. Keeping them face down, walk slowly and thoughtfully to nine people who seem ready, and give each person the paper you feel belongs to them. Explain what you are doing.

![]() Forgiveness is seeing the nail, drawing it out, and thanking the one who drove it in, for the valuable lesson he made possible.

Forgiveness is seeing the nail, drawing it out, and thanking the one who drove it in, for the valuable lesson he made possible.